http://thefield.asla.org/2016/01/29/arboriculture-art-ecology/#comment-14466

ARBORI(CULTURE): ART & ECOLOGY

January 29, 2016 — asla staff

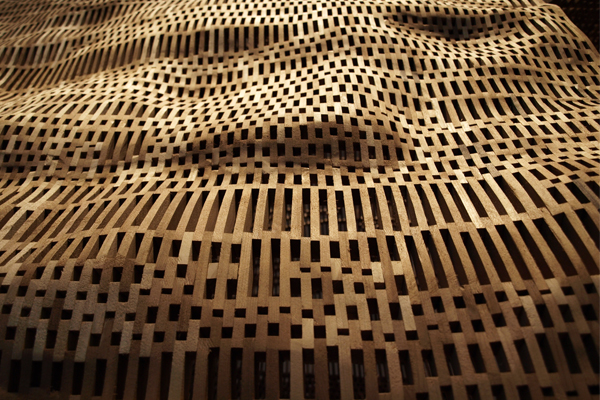

An interior view of John Grade’s Middle Fork installation at the Renwick Gallery

image: Alexandra Hay

image: Alexandra Hay

The speaker at a recent event at the Renwick Gallery in Washington, DC, was not an artist, curator, or art historian, but an arborist. Gregory Huse, Arborist and Tree Collection Manager for the Smithsonian Gardens, focused on John Grade’s Middle Fork installation in his talk, entitled “The Crossroads of Art, Nature and Ecology.” The piece consists of a tree, suspended sideways from the ceiling. Taking up the entire room, the sculpture is simultaneously massive and airy, moving slightly as visitors walk around it and shot through with light, evoking the dappled look of sunlight filtered through a forest’s leaves.

The Renwick Gallery, part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, reopened in November after an extensive two-year renovation with the exhibition WONDER. Middle Fork, in addition to installations by Maya Lin, Patrick Dougherty, and Janet Echelman, is one of the nine pieces included in this exhibition, which has drawn record crowds.

Middle Fork, located on the Renwick’s second floor, was built over the course of a year and was created from a plaster cast of a living tree—an old-growth hemlock growing in a forest near the middle fork of the Snoqualmie River in Washington. With the help of two arborists and nine assistants, plaster casts were taken of the tree’s trunk and limbs, from the root flare at the base up to a height of around 50 feet.

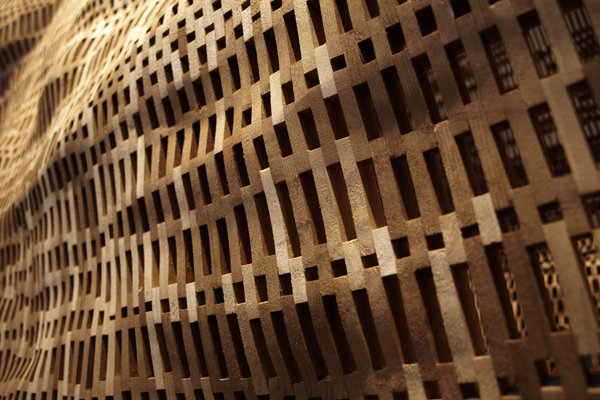

The casts were then transported to artist John Grade’s MadArt Studio in Seattle. There, hundreds of volunteers participated in constructing the sculpture. To create Middle Fork, Grade, his assistants, and numerous volunteers carefully placed thousands of salvaged cedar blocks around the plaster form, glued the blocks together, and then removed the plaster cast from inside, leaving just the web of cedar blocks, outlining the tree’s form in exacting detail.

Grade’s aim was to engage as many people as possible in the construction of the sculpture. Passersby were invited right from the sidewalk into the studio, located in Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood, to take part in the process.

The overall effect of these tiny blocks meticulously assembled into a massive whole is one of incredible detail that evokes every bump and curve of the tree. The final result is a “hollow, light-filled armature that holds the exact shape of the tree,” a perfect copy that also reflects the ephemerality of living things. Though an exact copy, the sculpture represents the particular moment in time when the cast was made, and no longer fits the tree—which continues to grow and change—from which it was molded.

Entering the installation, the first sight of the sculpture is from the root flare into the long interior—arborist Gregory Huse’s favorite view. From here, you “get a sense of the tree’s architecture from the inside out.” The perspective emphasizes how “every tree is completely unique.”

After the sculpture is no longer being exhibited, Middle Fork will be returned to the base of the hemlock tree from which it was made, to gradually disintegrate back into the soil and nourish the tree. The sculpture’s connection to nature and to the tree that gave it its form reflects the artist’s focus on the environment, and on our changing climate, which shapes much of his work.

Huse highlighted some of the changes that have taken place in recent decades, showing a comparison of the USDA Hardiness Zone Map from 1990 to 2006 that makes clear the northward shift of warmer zones. As these alterations in temperature and precipitation occur, life cycles are disrupted and the genetic fitness of populations changes. Trees and other species that once thrived in certain locations are no longer suited to these areas as shifts in climate, and subsequently in ecology, reshape the world around us.

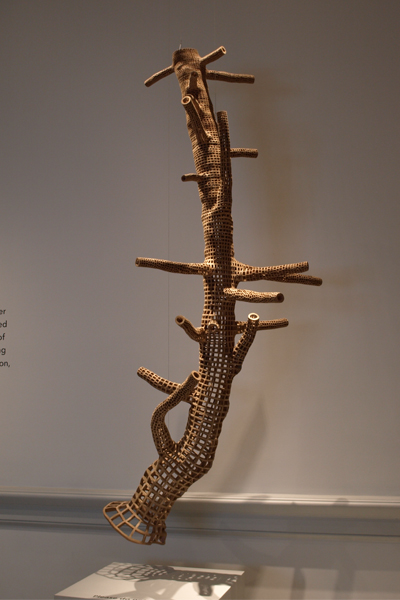

Downstairs in the Renwick is a second Middle Fork sculpture that offers a strong contrast to the larger piece. To create Middle Fork (Arctic), Grade traveled to northern Alaska and cast a rare balsam poplar that he found after days of searching. Though the casting and construction process for both sculptures was the same, the two could not be more different. Middle Fork (Arctic), though the same size as the whole tree Grade found, looks like a fragment—this could be a broken-off branch of Middle Fork (Cascades) or a small prototype for the larger installation. It gives viewers a contradictory sense of something fragile and feather-light, displayed in suspension, yet hardy enough to survive in the Arctic.

As the Smithsonian Gardens Arborist, Huse is responsible for maintenance of the Smithsonian’s trees, all located in the controlled urban environment of Washington, DC, structural pruning, and maintaining the Smithsonian Tree Collection in GIS, which in the future will be made available online for anyone interested in seeing the collection. Giving a lecture at the Renwick may have been an usual assignment, but an arborist’s view of an installation so closely tied to ecology and so clearly inspired by nature was a welcome surprise.

Artist John Grade will also be speaking at the Renwick on Sunday, February 28 about his Middle Fork installation. Even if you can’t make it to that event, WONDER is well worth a visit—the exhibition lives up to the name.

by Alexandra Hay, Professional Practice Coordinator at ASLA

No comments:

Post a Comment