https://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/lists/10-great-films-about-end-world

10 great films about the end of the world

…or how we learned to stop worrying and love films about impending apocalypse.

The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961)

The film begins with a man walking through the deserted streets of London – quite a cinematic coup in itself, conjuring up an unnerving sense of reality gone wrong. We then flash back to discover what has happened and find out that ill-advised nuclear tests have knocked the Earth out of its orbit and sent it moving towards the sun. Initially, the British public enjoy the scorching weather, but, as the Earth gets hotter, a state of emergency is declared and scientists search for a solution.

|

10 to try Each of the recommendations included here is available to view in the UK. |

Ever since the days of silent cinema, filmmakers have realised that disaster is good box office and what better disaster to set the tills ringing than the end of the world and civilisation as we know it? From 1950s science fiction to millennial European angst, apocalypse has time and again reared its fiery head and attracted the attention of some of cinema’s finest talents…

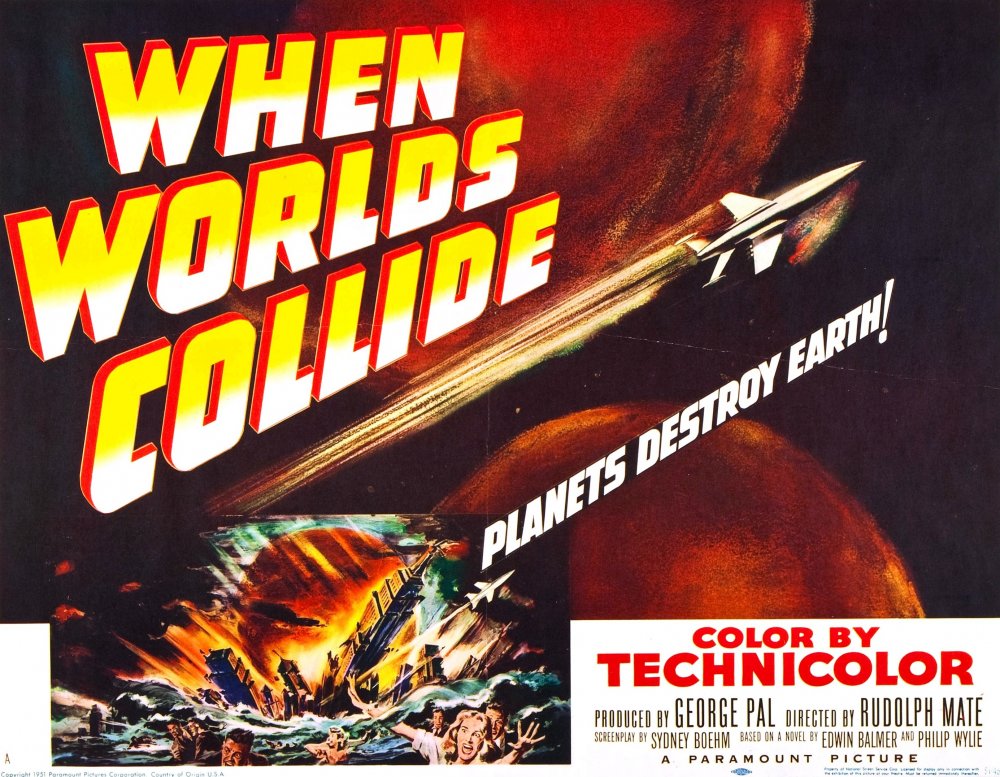

When Worlds Collide (1951)

Director Rudolph Maté

When Worlds Collide (1951) poster

The narrative is shaky and the science even more so, but the special effects, notably the flooding of Times Square by a tidal wave, remain highly entertaining and manage to overcome the limitations of the acting and dialogue. The worlds finally collide on a monitor screen, Earth flaming like Dante’s inferno as it’s swallowed into the monolith-like star.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

Director Stanley Kubrick

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

Meanwhile, the eponymous doctor (also Sellers), inventor of the Earth-threatening Doomsday Machine, finds the idea of apocalypse sexually stimulating and the pilot delivering the bomb rides it into eternity like a bucking bronco. Vera Lynn sings ‘We’ll Meet Again’ as the mushroom clouds multiply.

- Celebrating Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove at 50

- Behind the scenes: Dr Strangelove

- Rare images of the Dr Strangelove custard pie fight

The Quiet Earth (1985)

Director Geoff Murphy

The Quiet Earth (1985)

When he discovers two other survivors – a man and a woman – we seem to be on course for a rerun of the love triangle of The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959), but Murphy’s film is far more interested in a study of one man’s own personal apocalyptic, dreamlike apotheosis, which culminates on a deserted beach in the face of the awesome beauty and destructive potential of nature. The ambiguity of the film can strike some viewers as infuriating but the eerily effective location shooting on the deserted New Zealand streets offers a potent sense of a time after everyday life has simply stopped.

The Sacrifice (1986)

Director Andrei Tarkovsky

The Sacrifice (1986)

There’s a potent feeling of spiritual isolation here but also a sense of transcendence and healing, particularly in the character of Little Man, the hero’s son, who is mute right up until the final moments. Nor is it depressing to watch; the intellectual turbulence behind what was a final statement by the dying Tarkovsky is endlessly fascinating.

When the Wind Blows (1986)

Director Jimmy Murakami

When the Wind Blows (1986)

Jimmy Murakami’s film, simply but elegantly animated, is one of the grimmest, most heartbreaking films about nuclear Armageddon simply because it is so fundamentally parochial in its concerns. The couple’s heroism lies in their unassuming courage and sustaining love despite the impending tragedy. Particularly powerful is the suggested contrast between the memories of the moral certainties of the Second World War and the insane randomness of Mutually Assured Destruction.

The Rapture (1991)

Director Michael Tolkin

The Rapture (1991)

The film is blisteringly powerful and disturbing, centred almost entirely upon a painfully credible performance from Mimi Rogers as Sharon, a former swinger who becomes a born-again Christian upon being told that the final judgement is nigh. But things go wrong and we’re left with a film that raises more questions than it answers. The final scene, showing spiritual and physical desolation, is cruelly logical in its implications about exactly who “the chosen ones” might be.

Last Night (1998)

Director Don McKeller

Last Night (1998)

The exceptional performances – including David Cronenberg in a rare appearance in front of the camera as the owner of a power company ringing all his clients to thank them for their custom – give us a real sense of empathy for these wonderfully normal people whose resilience in the teeth of hopelessness is inspiring and moving. The final scene, where love unexpectedly overcomes despair and crowds celebrate their ultimate destruction, is bizarrely uplifting.

Donnie Darko (2001)

Director Richard Kelly

Donnie Darko (2001)

In terms of the world ending, it doesn’t quite pay off in the way you might expect. But this is certainly a very personal cataclysm and it reminds us of a scene in the film version of Graham Swift’s Waterland when the narrator tells us that the world can end in many ways, “as many ways as there are people”.

Melancholia (2011)

Director Lars von Trier

Melancholia (2011)

Right at the start of the film, we see what is going to happen at the end and this knowledge casts an ironic shadow over the events we see portrayed, which are often sharply funny and occasionally wounding in the case of the behaviour of the girls’ parents. Kirsten Dunst and Charlotte Gainsbourg are astonishingly powerful as the sisters and the apocalyptic conclusion, backed by music from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, is madly, wildly beautiful.

Take Shelter (2011)

Director Jeff Nichols

Take Shelter (2011)

Throughout, the sense of impending disaster amid the beautifully shot broad Ohio fields and the endless blue air is compellingly sinister and the everyday details of a life lived with the burden of foreknowledge are completely credible. Equally frightening is the sense of a social infrastructure that’s woefully inadequate to cope with disaster.

Your suggestions

The Road (2009)

- The Road (John Hillcoat, 2009)

- Threads (Mick Jackson, 1984)

- 4.44 Last Day on Earth (Abel Ferrara, 2011)

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegel, 1956)

- 12 Monkeys (Terry Gilliam, 1995)

- On the Beach (Stanley Kramer, 1959)

- Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (Lorene Scafaria, 2012)

- The Cabin in the Woods (Drew Goddard, 2012)

- The War of the Worlds (Byron Haskin, 1953)

- The Turin Horse (Béla Tarr, 2011)

No comments:

Post a Comment